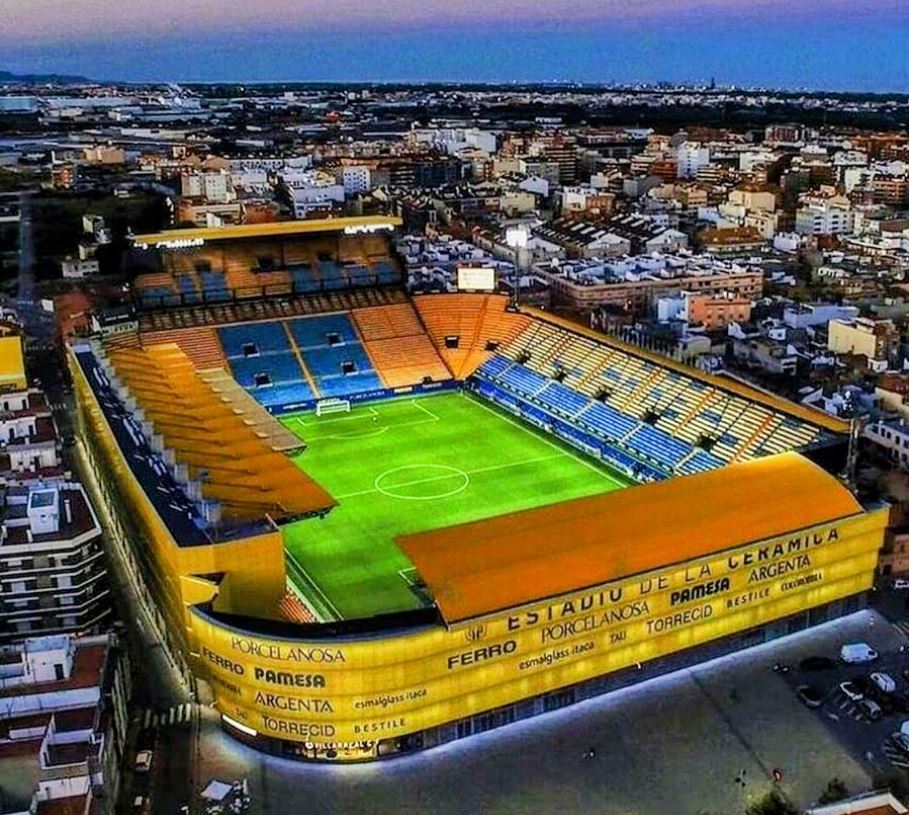

On the coastal plain close to Castellón de la Plana, around five miles inland from the Mediterranean Sea, lies a stadium so conspicuously larger than any of its surroundings that it resembles a grounded cruise ship, dwarfing all around. This is the Estadio de la Cerámica (I’ll refer to it by its historical name, El Madrigal, from here on in), a 23,000-seat arena in a town of 51,000 inhabitants. It is home to Villarreal Club de Fútbol, the small-town team made big thanks to the foresight and money of ceramic tile magnet Fernando Roig.

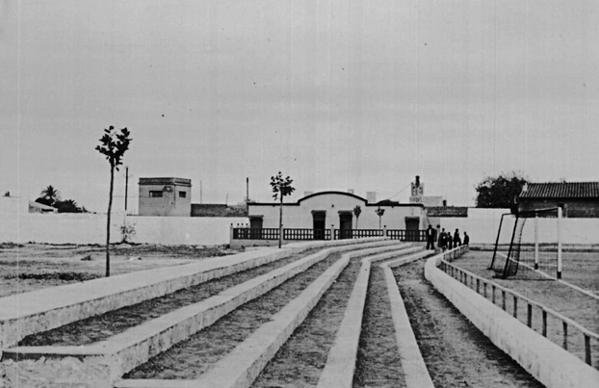

The first team to emerge from the town was Club Deportivo Villarreal who were founded on 10 March 1923 and was resident at El Madrigal from 17 June of that year. CD Villarreal did not have the honour of inaugurating their own ground, which fell to local big-wigs CD Castellón and another team from Castellón, Cervantes. To be frank, it wasn’t much to look at, being essentially a fenced-off field with shallow terraces. CD Villarreal did win the Primera Regional in 1936 and faced a playoff for a place in La Segunda against FC Cartagena. They lost 3-6 on aggregate, and following the cessation of football due to the Civil War, the club folded. The current club was founded on 25 August 1947, going by the strange name of Club Atlético Foghetecaz. The name was created from the surnames of the founding members but eventually changed to Villarreal Club de Fútbol in 1956.

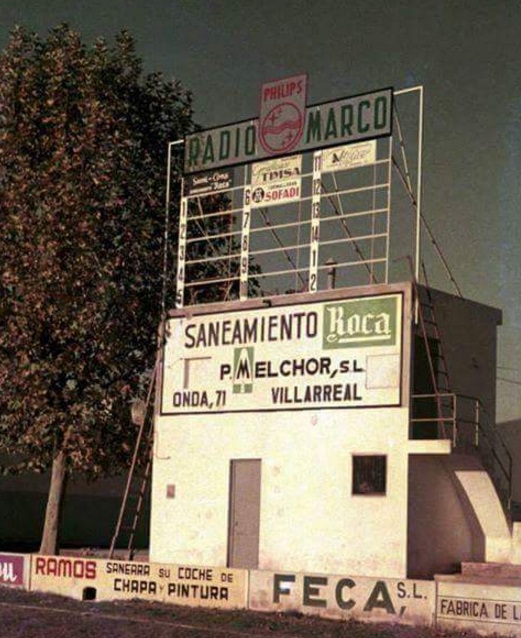

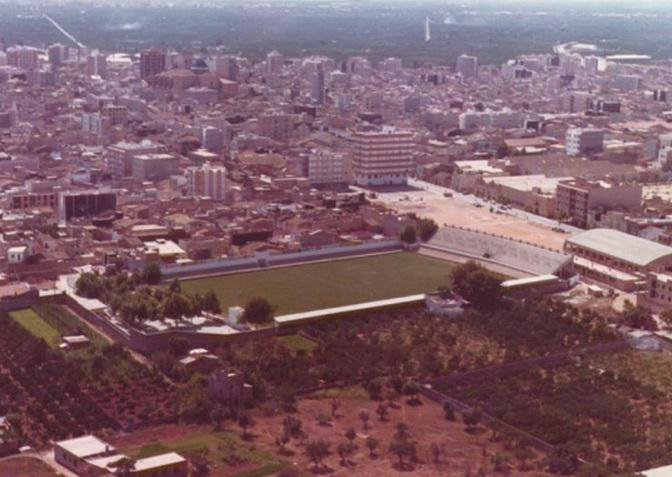

To get an understanding of what Villarreal CF was like before Roig appeared on the scene, you don’t have to go back that far. All that you see at El Madrigal has been built since 1998. Go back another ten years and El Madrigal was a presentable, but small stadium, perfectly acceptable for a club that had spent the vast majority of its history in the Tercera and regional leagues. El Madrigal was first extended during the summer of 1952 when the pitch was enlarged, and more substantial terracing was added. The 1960s saw a small covered stand erected along the northwestern side of the ground, and another tier was added to the southwestern end terrace in 1972 when Villarreal reached La Segunda for two seasons. Thanks to funds from the Municipality, floodlights were added and these were switched on for the first time for a match against SE Eivissa on 16 September 1973. In 1988 the small main stand was demolished, and a more substantial structure took its place. This full-length cantilevered stand was officially opened on 8 March 1988 with a friendly against Atlético Madrid.

By now, Villarreal was playing its football in Segunda B, but after two successful seasons at this level, the club was relegated back to the Tercera at the end of the 1988-89 season. The stay was brief, however and after finishing second in the regular season, the club had little problem finishing top of their play-off group ahead of CF Balaguer, CD Imperial & C.D. Cala d’Or. Back in Segunda B for the 1991-92 season, any thoughts of consolidating their position went out the window with a second-place finish and entry into the end-of-season playoffs. Here they came up against UD Salamanca, Real Linense Balompedica and Girona CF, and after losing rounds 3 & 4, it appeared the chance of promotion had disappeared. However back to back-to-back victories over Real Linense saw the club prevail and return to La Segunda for the first time in 20 years.

The club held its own in La Segunda during the 1990s, never really troubled by relegation, but not figuring in the promotion shake-up either. Then, in 1997, Roig arrived and turned the club and the stadium on its head. He completely restructured the set-up with a player-loan agreement put in place with Valencia CF, the building of a Ciudad Deportivo a kilometre to the west of the stadium, new youth teams and a substantial transfer budget. El Madrigal changed as well with the southeast stand extended and a slim cover added, both ends of the enclosure developed and most significantly, a new stand was built on the northwest side. The players’ changing rooms are now located in the main stand, but over the years, they have been dotted around El Madrigal. Firstly in the southeast corner, then from 1936 in a building to the northeast, then in 1998 under the southwest stand with the entrance in the southwest corner.

The impact on the pitch was immediate, and after finishing the 1997-98 season in fourth place, they entertained SD Compostela in a promotion/relegation playoff. After a 0-0 draw at El Madrigal, Villarreal returned from Galicia with a 1-1 draw and victory on away goals. La Primera had been reached seven seasons after leaving the Tercera. But if you live by the sword you can also get quite an unpleasant cut from it as well. 12 months later Villarreal found themselves back in the promotion/relegation playoffs, this time after finishing eighteenth in La Primera. Sevilla FC made short work of them, winning 3-0 on aggregate. Many thought that would be the last that La Primera would see of The Yellow Submarine (the club’s nickname), but Roig had different ideas.

A third-place finish in La Segunda in 1999-00 saw the club return to La Primera after a one-year absence. Season 2000-01 saw the club finish seventh, one place and two points off a European place. The next two seasons were, however, a struggle, with two fifteenth-place finishes. Keen, however, to broaden their experience, Villarreal entered and won the Intertoto Cup in 2003 and 2004. That last victory in the Intertoto Cup was under the guidance of new manager Manuel Pellegrini, and under his tutelage, the club was about to top all that had gone before. A third-place finish in 2004-05 earned the club a place in the Champions League and, but for a penalty miss by Riquelme in the final minute of the semi-final, the fairy tale may have been completed.

Entry into the Champions League led to further development of El Madrigal, with the pitch being lowered a couple of meters, dressing rooms renovated, and new media facilities installed. The most striking addition, however, was at the north-east end of the stadium. Just when you thought that El Madrigal couldn’t get any bigger, the club added a covered amphitheatre to the top of the already substantial single deck. This elevated stand is where travelling supporters are housed on big European nights and ‘Category A’ Primera matches.

Then, in the space of nine months, it all went horribly wrong for Villarreal. The club that hadn’t finished outside the top ten in the previous eight seasons endured a wretched 2011-12 season at home and in Europe. The injuries to key players played their part, as did the lack of goals, but the nature of their relegation, losing to a late goal from an Atlético Madrid club that still owed Villarreal millions in transfer fees, appeared particularly unjust. There are plenty of examples of clubs who have lived the dream and then fallen on hard times, but the Yellow Submarine was not about to sink without a trace. After a slow start to life back in La Segunda, form improved and promotion back to the top tier was secured after a 12-month absence.

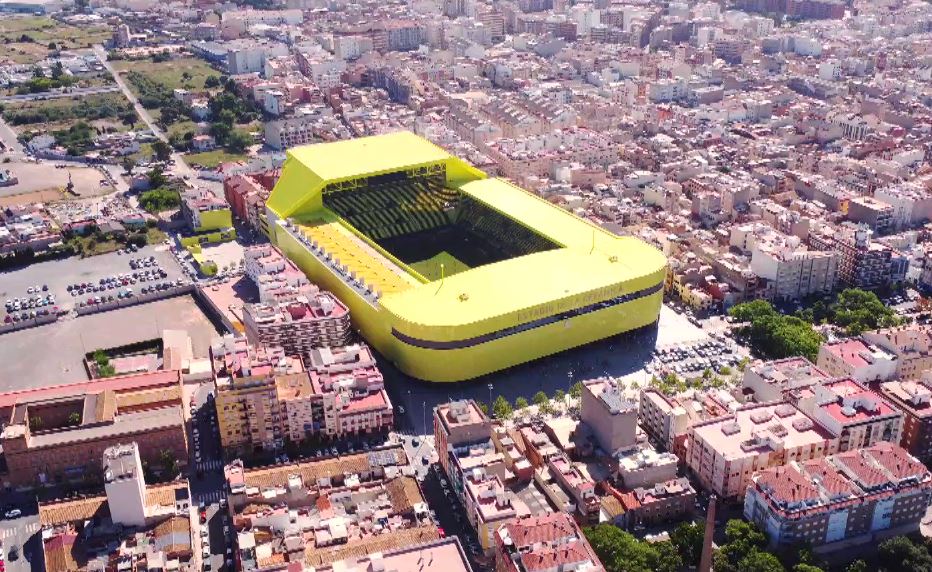

It came as no surprise that Villarreal’s return to the top flight saw the club record a series of top 6 finishes and qualify once again for the Champions League. Work continued at El Madrigal, with the addition of new corner stands and the exterior of the stadium renovated and clad in ceramic tiles. This was part of a deal that saw Villarreal sell the naming rights of El Madrigal, and from January 2017, the stadium was known as the Estadio de la Ceramica. However, if you thought that the stadium was more than adequate for a provincial club with a 18,000 fan base, then you were mistaken. El Madrigal was about to get super-charged.

In February 2002, the club announced that to mark the stadium’s centenary, €35m would be spent on modernising their home, with the principal aim of providing cover for all four stands under an undulating roof. The renovation started in May, with the goal of the club being back home at the mid-point of the 2022-23 season. As the club moved out and started the new season at Levante UD’s recently redeveloped stadium, El Madrigal was gutted, and a huge steel canopy rose above its paired-back stands. The project was part-funded by the cash injection from La Liga’s deal with CVC Capital Partners. Unfortunately, costs rocketed, particularly the price of steel, and whilst the project’s timeline was met, the budget took a pounding. On 31 December 2022, Villarreal hosted Valencia CF back at El Madrigal, and whilst it took a further four months to finish the yellow-clad exterior, the extraordinary transformation was already clear to see.

At a final cost of €70m, and with no increase in stadium capacity, it would be easy to dismiss the redevelopment as folly. However, that misses the point. Villarreal could have opted to move to a new, out-of-town site and built a larger stadium, but that would have lacked the history and intimacy that El Madrigal has in abundance. Instead, they have chosen to remain right at the heart of the community, in a genuinely unique stadium, which is more than can be said of many of the new build, identikit stadiums. For that alone, Villarreal should be commended. Just don’t ask me to call it the Estadio de la Cerámica! ; )