“There are stadiums great by reputation and association which, when first encountered, disappoint. The Camp Nou is not among them”. These are the words of architectural historian Simon Inglis, but I have to admit that from a distance, I was a little underwhelmed by the Camp Nou. Then in 2012, I paid my first visit, and I got it loud and clear. During the few hours I spent wandering around the stadium, the museum and the whole complex, I started to comprehend the size, the history, the symbolism and above all, the fact that Fútbol Club Barcelona is “Més que un club”.

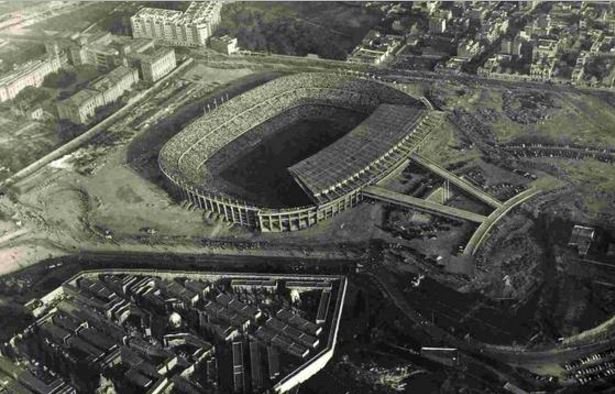

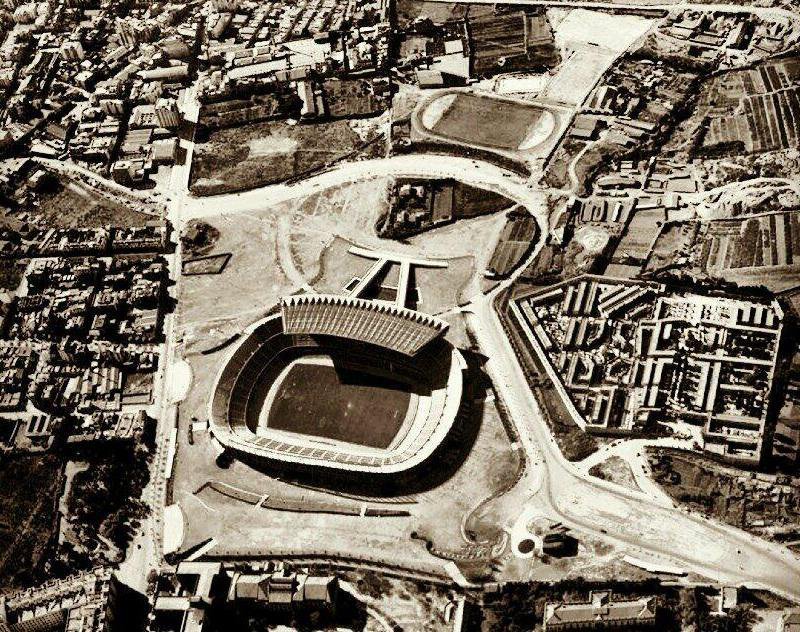

Back in the early 1950s, when the Camp Nou was first conceived, there was something of a stadium boom taking place in Iberia. First off the mark was Real Madrid with their new stadium at Chamartin (It was opened in 1947, but was extended in 1953). Portuguese giants Benfica opened their Estadio Da Luz in 1954, and supporting acts were provided in the form of Sevilla’s Estadio Ramón Sánchez Pizjuán and Sporting Lisbon’s Estadio José Alvalade. Barça, even with their souped-up version of the Camp de Les Corts and its 60,000 capacity, were wary of being left behind and very nearly over-committed to the building of the new stadium, which in part, led to the barren years on the pitch during much of the 1960s. The first stone at the Camp Nou was laid on 28 March 1954, and the proposed 66 million peseta project was to be financed entirely by club socios. Designed by local architects J. Soteras Mauri & F. Mitjans Miro, it would feature two huge tiers and a modern cantilevered roof over the west side.

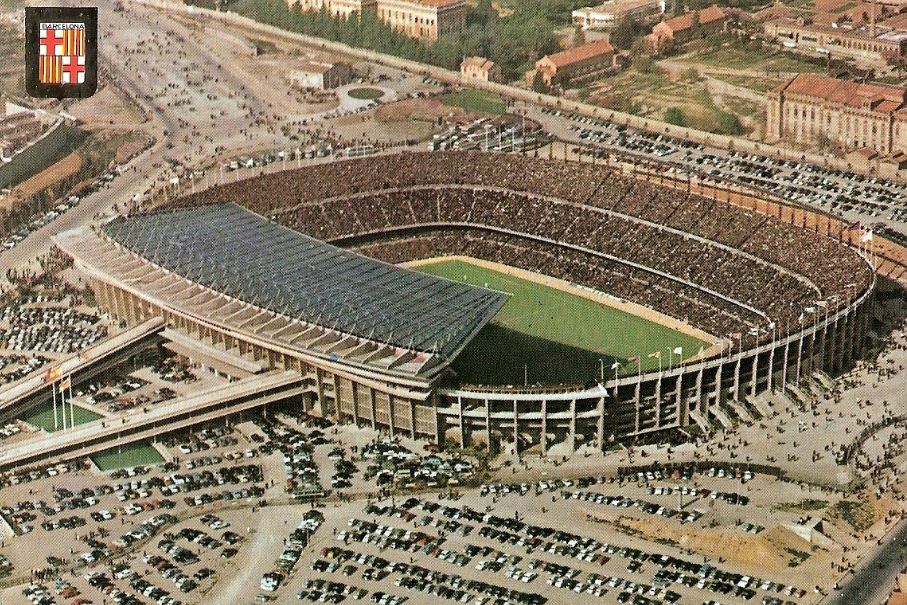

The final years at Les Corts were very productive and saw the club win the league on two occasions (1952 & 53) and the cup on four occasions, including the 1957 final win against local rivals Espanyol at Montjuic. Finally, on 24 September 1957, the stadium was inaugurated with a match against a Warsaw Select XI, which Barça won 4-2. 12 days later, the Camp Nou hosted its first official league match, when Barça put Real Jaén to the sword, winning by six goals to one. The new stadium, with its 90,000 capacity, had taken 3½ years to build and finally cost 288 million pesetas, an almost ruinous 425% over budget. Two years later, on 23 September 1959, the first floodlights were switched on for the European Cup tie against CSKA Sofia. Initially, the team’s form matched their impressive surroundings, with league titles in 1959 & 1960 and Copa del Rey victories in 1959 and 1963, but with an ageing side and talisman, László Kubala switching to Espanyol, the remainder of the sixties and early seventies were barren years on and off the pitch.

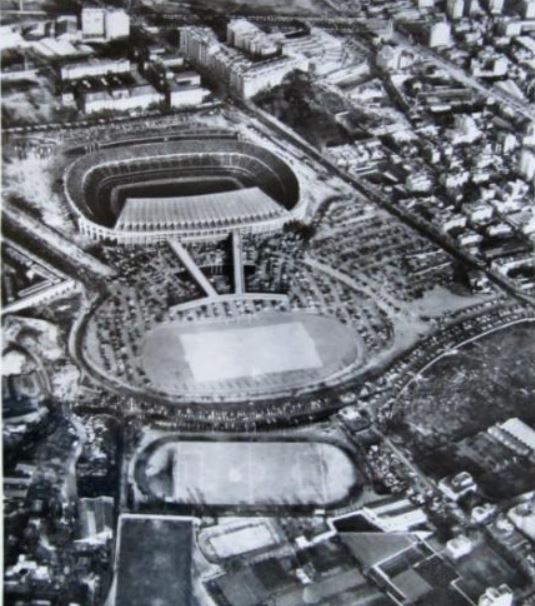

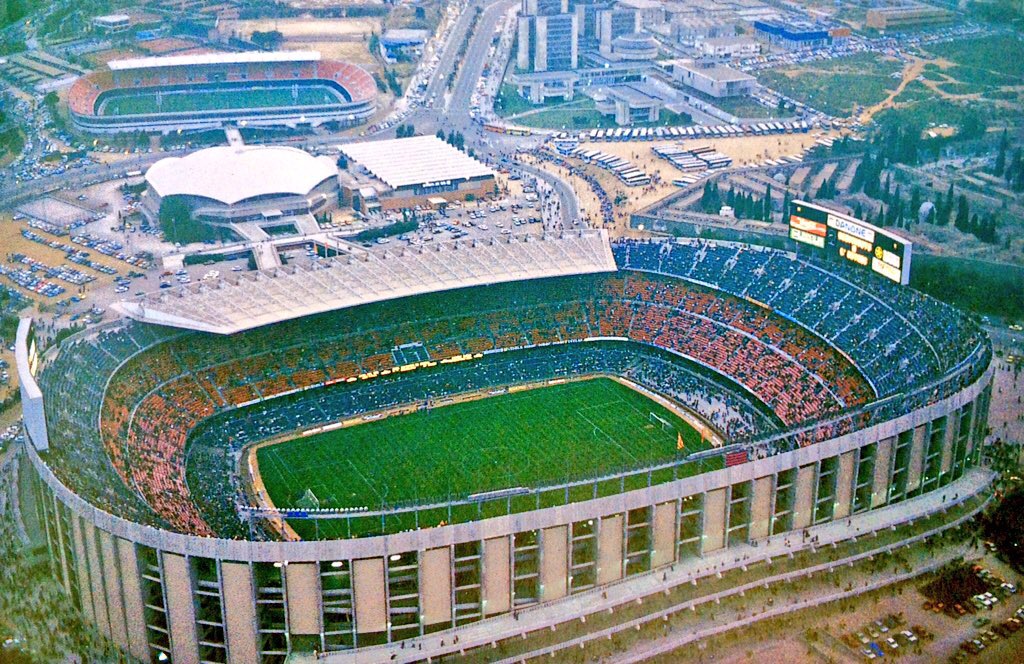

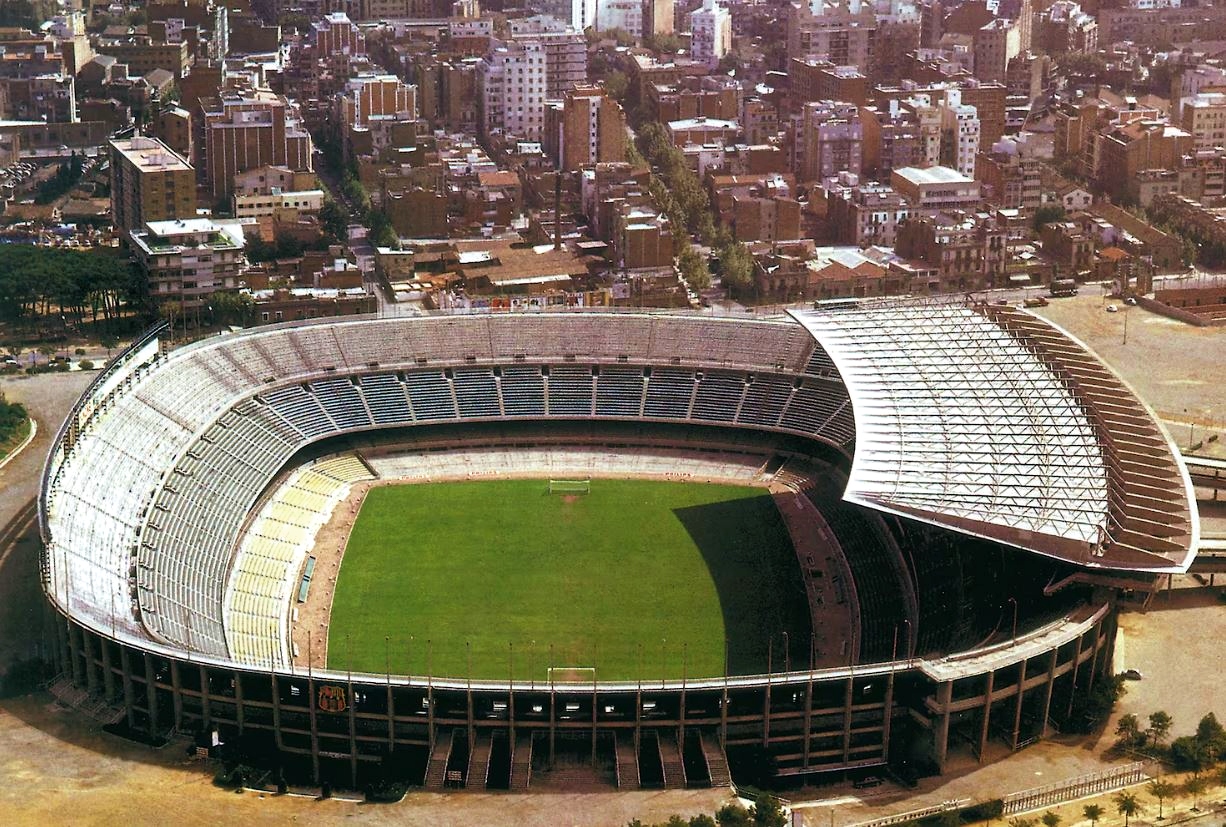

Club finances were not helped by the protracted saga that surrounded the sale of Les Corts. When it was finally sold in 1967, all of the 226 million pesetas raised was used to pay off the club debt. With the club’s finances back under control, the club set about rebuilding the team and developing the next stage of the sports complex. 1971 saw some significant changes. The first was the building of the Palau Blaugrana, an indoor sports hall, and an Ice Rink. This would be home to the club’s basketball, handball, volleyball, roller hockey & ice hockey teams, and generate valuable additional revenue as a concert arena. On the pitch, the great Dutch coach Rinus Michels was employed, and thanks to his persuasive powers, Johan Cruyff chose Barça ahead of Real Madrid. The league title returned to the Camp Nou at the end of the 1973-74 season, and the Copa del Rey followed three years later. As for the stadium, except for two electronic scoreboards, it remained unaltered until the lead up to the 1982 World Cup.

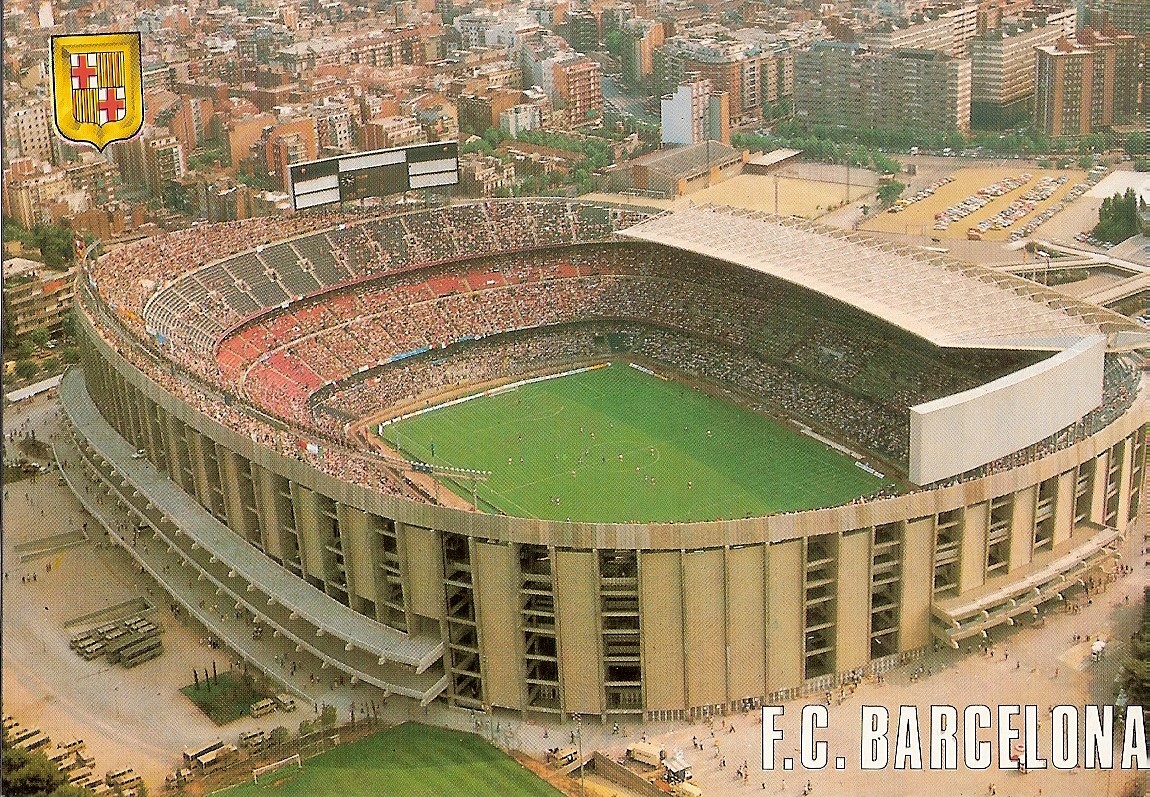

The Camp Nou was chosen to stage the opening match at Mundial ’82, along with three second-round matches and a semi-final. In 1980, a major reconstruction project began, which would result in the capacity increasing to 120,000. At a cost of 1,298 million pesetas, an additional third tier was added to the three uncovered sides, along with new scoreboards and floodlights. A plaque in the upper foyer commemorates the opening of the remodeled Camp Nou, which saw Belgium defeat then world champions Argentina 1-0. The crowd of 95,000 was the highest of any of the matches staged at the Camp Nou, in what was generally a poorly attended World Cup. Not that Barça was complaining; they had increased the size of the stadium, and for once, it didn’t damage the club’s coffers. To round things off, 250 metres to the west of the stadium, the club built another, albeit smaller stadium, the Mini Estadi.

The Camp Nou was now Europe’s largest and most prestigious sporting venue, and during the eighties, it saw its fair share of sporting and non-sporting activity. Under the tutelage of Terry Venables, the league title was captured in 1984-85 and the Copa del Rey in 1986. Pope John Paul II paid a visit in November 1982 and became a member of the club, and practically every 1980s pop icon seemed to play the stadium. Then, with Barcelona winning the right to stage the 1992 Olympiad, the Camp Nou was chosen to host the final of the football tournament. The 1992 Olympic soccer tournament also saw matches staged at Espanyol’s Sarrià stadium, Sabadell’s Nova Creu Alta, Real Zaragoza’s La Romareda and Valencia’s Mestalla. but it was Spain’s memorable last-minute victory over Poland in the final that capped a hugely successful Olympiad for Barcelona.

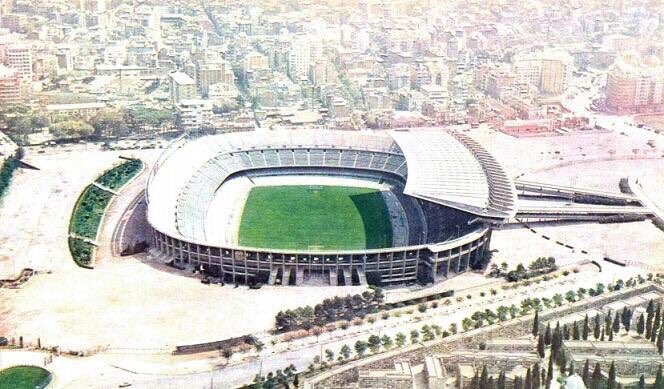

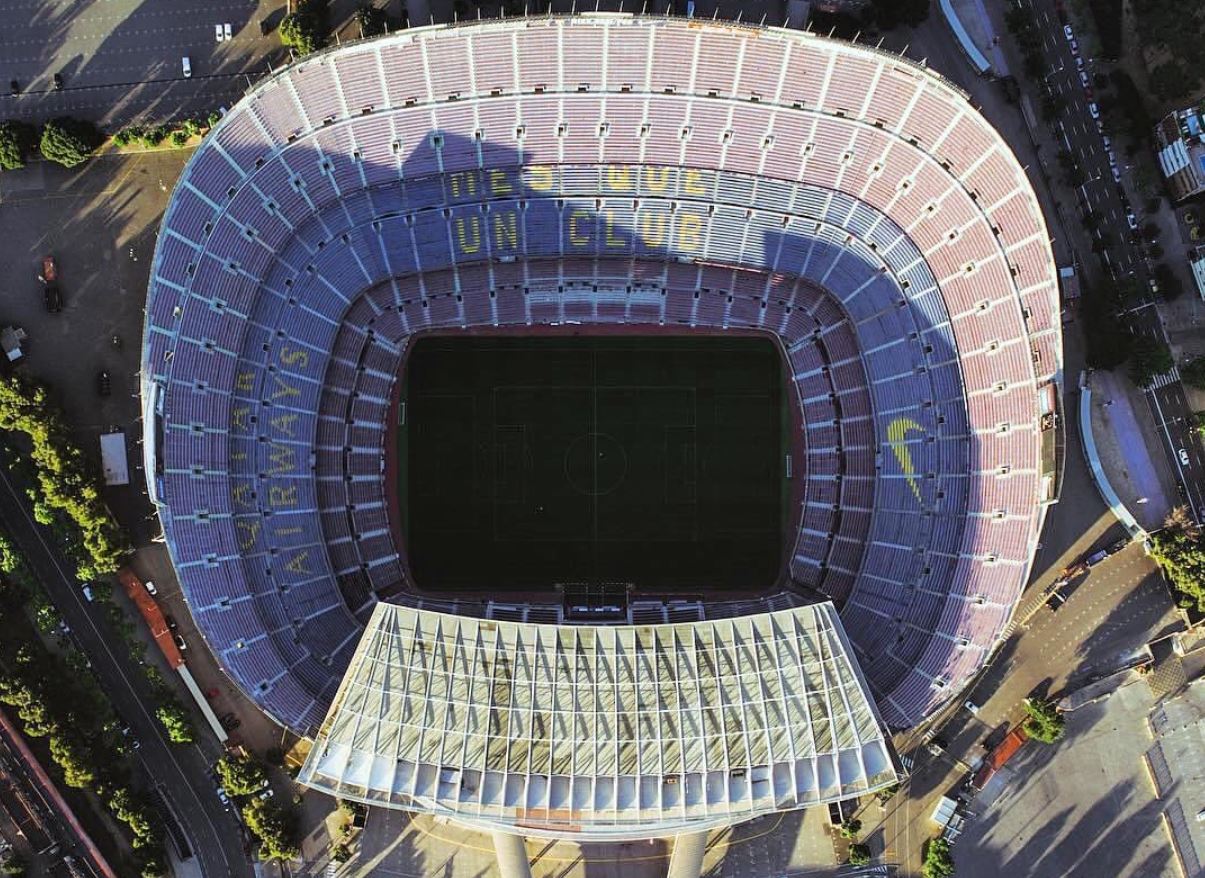

In 1993, Barça started the process of turning the Camp Nou into an all-seater arena, but to achieve this and ensure that the lowest tier of seating had decent sight lines, the pitch was lowered by 2.5 metres. This also involved removing the popular standing areas from behind the goals, much to the chagrin of the notorious Boixos Nois supporters. The addition of seats to the lower tiers saw the capacity drop to 115,000, and this dropped a further 15,000 when the upper tier was seated in 1995. The lighting and sound systems were upgraded during the 1998-99 season and the stadium was awarded UEFA 5-star status prior to hosting the memorable 1999 Champions League Final.

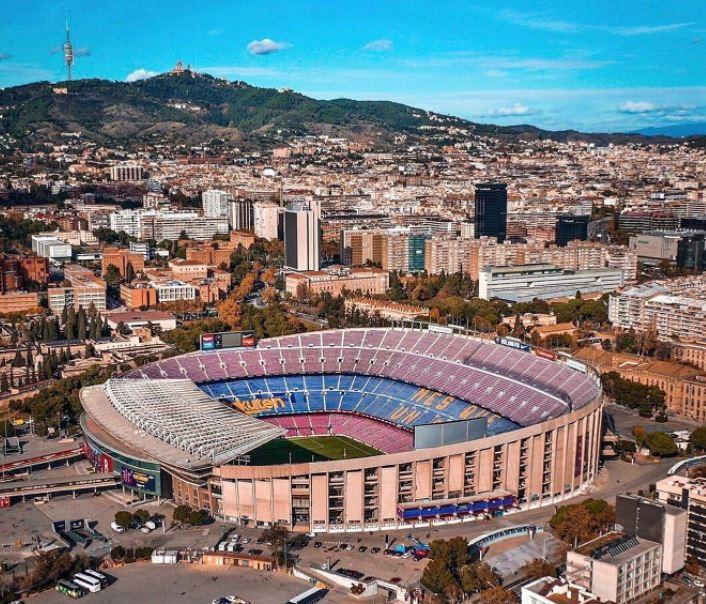

When I first paid a visit back in 2012, I showed a great deal of restraint, spending a good hour looking around the whole complex. Arriving via the subway to the north, you get a better feel for the size and layout of the empire. The access ramps to the main stadium were in front of you, and to the right was the Palau Blaugrana, which had a capacity of 6,400. Further to the right stood the Mini Estadi, but this was demolished in 2019 to allow more space for the redevelopment of the main stadium. The reserve side now plays at the Estadi Johan Cruyff out at the club’s training complex in Sant Joan Despí. Dotted around the 16-hectare complex were training pitches and outdoor tennis and handball courts. Wander back past the stadium (I said I showed restraint!), past the cemetery of Les Corts and amid all this urban architecture, you will find a farmhouse. This is La Masia, built in 1702 and for 20 years the club offices, then from 1979 to 2012, it was the headquarters of the club’s youth academy, before it also moved out to the club’s training complex.

Structurally, very little changed at the Camp Nou following the 1993 redevelopment. There is the perennial changing of the colour & configuration of the seats, but when you have over 99,000 of them, it must seem to be a never-ending job. There was, of course, talk of rebuilding or starting afresh elsewhere. For example, in 2007, British architect Sir Norman Foster’s design won a competition to renovate the Camp Nou. At an estimated cost of 250 million euros, the plan included the addition of 7,000 seats for a maximum capacity of 106,000. To finance this, the board approved the sale of the land on which the Mini Estadi stood, but in 2009, just before work was due to begin, the project was halted, thanks to the world financial crisis and subsequent fall in real estate prices.

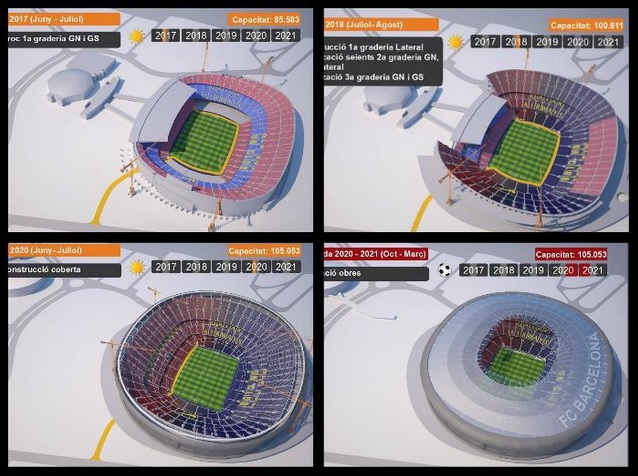

As Barça started an era of unparalleled success on the pitch, talk of redeveloping the Camp Nou was put on the back burner. Everybody knew that this iconic structure was outdated and lacked little of the commercial and media infrastructure that so many of its competitors had. But whilst the team remained all-conquering, little else seemed to matter. Then, just as Barça’s infallibility was starting to be questioned, and with news emerging of Real Madrid’s imminent redevelopment of the Santiago Bernabéu, the club’s board made an announcement. In January 2014, plans were released detailing a €600m redevelopment of the stadium, which would tackle the principal problems of sight-lines, cover and corporate revenue. With a proposed capacity of 105,000, the Camp Nou would have the highest seated capacity in Europe.

The redevelopment would see the realignment of the lower tier, addressing the shallow rake of the seats, which has proved problematic since the pitch was lowered in 1993. A new ring of corporate boxes will be built, which will add 3,500 VIP seats along with restaurants and improved media facilities. The North & South Grada’s will be extended, rounding off the ends that tapered down towards the main stand. The old roof was to be removed and another tier added to complete the bowl. A ring of roof piles will be incorporated within a new exterior, and finally, a 3-ringed cantilevered roof was to be constructed to cover all four sides of the stadium. All very good on paper and in a slick video presentation; however, the reality was very different. Barça’s debt rose to over €1 billion, and as great players moved on or retired, the seemingly endless flood of trophies turned into a trickle. The start date of the redevelopment kept being pushed back, first, it would be 2017, then it would start 2019. There was also chaos in the boardroom, which paved the way for Joan Laporta to return as president in March 2021. Throughout this 7-year period, the only physical evidence of the the project was the demolition of the Mini Estadi.

Laporta’s latest tenure started with a number of controversial decisions that focused on restructuring the club’s dire finances. Perhaps the most contentious came in July 2022 when the club signed a deal with music streaming service Spotify, which handed over the naming rights of the stadium for four years in return for €295m. Laporta also confirmed that the renovation work would commence in June 2023. Demolition of the upper tier actually started during the 2022-23 season when a section of the southern end was removed. Barça also announced that they would play the 2023-24 season at the Estadi Olímpic Lluís Companys up on Montjuic, but their aim was to return to the Camp Nou before the end of 2024. On 28 May 2023, a crowd of 88,775 gathered to watch Barça defeat Real Mallorca 3-0 in the final game at the Camp Nou before work commenced on its significant upgrade.

Whilst work continued on the redevelopment, the Camp Nou was included in Spain’s list of stadiums for its joint hosting of the 2030 World Cup. Unfortunately, a number of deadlines for the club’s return to the stadium were missed, and it appears that Barcelona will spend two full seasons away from their home. However, when they do finally return, the stadium will continue to resemble a building site. Work is scheduled to continue until the summer of 2026, whilst the upper tiers and roof grow around the action on the pitch. Barcelona is not out of the financial mire by any stretch of the imagination, but there have been times over the past decade when it looked like it would be the club and not the upper tiers of the Camp Nou that would come tumbling down.