Article updated: 03/12/2025

I can’t help liking Real Betis. It might be their role as underdog or their regular switching between divisions. It could also be their classic green & white striped shirts, or given my soft spot for unusual stadia, their ridiculously proportioned home, the Estadio Bentio Villamarin. Yes, there is a lot to like about Betis, not least their history, which is punctuated with triumphs & calamities, along with a sprinkling of farce.

The club was founded by students from the local Polytechnic Academy on 12 September 1907. They were originally called España Balompié (Balompié being derived from the Spanish translation of ball & foot – balón & pie) and set up home at the Campo del Huerto de Mariana. In 1909, they moved to the Campo del Prado de Santa Justa, changing their name to Sevilla Balompié. They were on the move again in 1911, switching to the Campo del Prado de San Sebastián, which was an area of open parkland also used by many of the city’s clubs, including their eternal rivals, Sevilla FC. In 1914, the club absorbed several smaller teams, including Betis Foot-Ball Club, which had been formed by disgruntled members of Sevilla FC. The merger led to the club changing its name to Real Betis Balompié after receiving royal patronage on 17 August 1914. The club continued to use the Campo del Prado de San Sebastián until 1918, when it moved to its first substantial home, the Campo del Patronato Obrero.

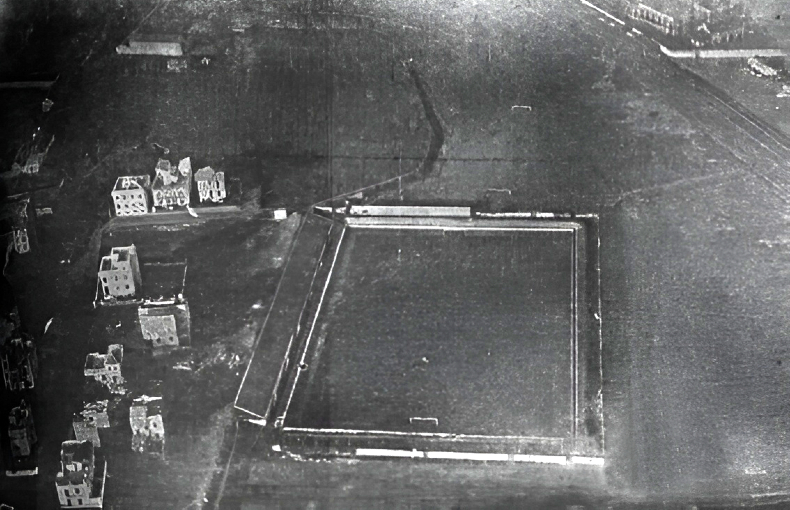

The move was necessitated by the local council’s decision to extend the Feria de Abril, using much of the Prado de San Sebastián. Without a home, the council leased a plot of land to the club, La Huerta del Fraile, which was in the current-day Barrio of Porvenir. It was close to the Sevilla-Cádiz railway line, and the area was highly industrialised with factories and a power station among the club’s neighbours. It was also close to the Real Patronato Obrero, a social housing society that had built 74 homes for destitute workers. The backgrounds of Betis and Sevilla were very similar, primarily consisting of affluent society types, who were the only ones with the time and money to play the game. However, from this point onwards, with Sevilla relocating to the Campo de la Reina Victoria (leased by the Spanish Royal Family), Betis was perceived as the club of the working classes.

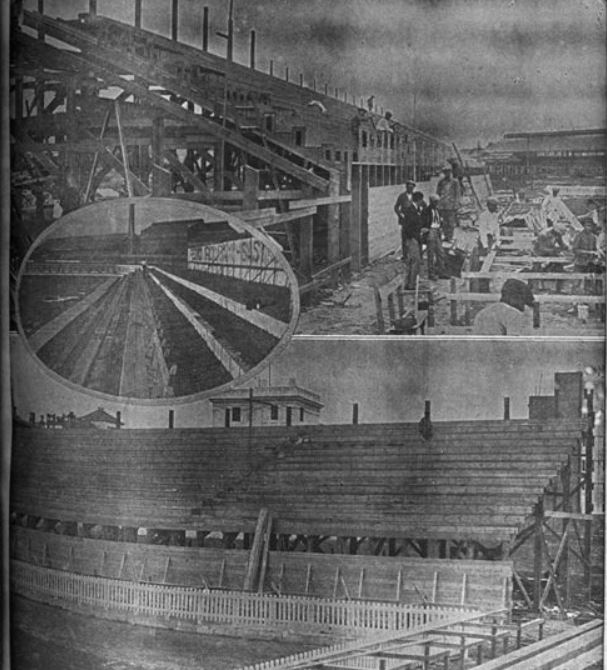

The Campo del Patronato Obrero was basic, and the club, short of funds, used old tables & doors to ensure that the pitch was enclosed. The first match at the new ground took place on 1 November 1918 with Betis playing against Sevilla FC, who ran out 1-5 winners. For the first few years, players changed in a small clubhouse located on the halfway line on the west side of the ground. Fortunately for Betis, there were happier times ahead. The Campo de Patronato Obrero underwent a major overhaul in 1924, which saw the development of a full-length, two-tiered open stand on the west side and a narrow open terrace on the east. The redevelopment was marked with a friendly against US Sants de Barcelona on 13 December 1924. In 1928, under the presidency of Ignacio Sanchéz Majias, Patronato underwent further redevelopment. The main west stand gained an 80 metre-long propped roof, and the northern & southern ends were terraced. An elaborate scoreboard was added to the rear of the north terrace, behind which the club built tennis courts. This latest phase of development increased the ground’s capacity to 9,000 and heralded a golden age for the club.

Betis won the Andalucian championship in 1928 and was a founder member of La Segunda in 1929. In 1931, Betis became the first club from the south of the country to reach the final of the Copa, losing 1-3 to Athletic Club at Real Madrid’s Campo de Chamartín. Betis won La Segunda title in 1932 and thus became the first club from the south of the country to play in the top tier of Spanish football. However, this was all eclipsed by the achievement of the 1934-35 season. Under the stewardship of Irishman Patrick O’Connell, who had been at the helm since 1931, Betis had developed a strong defensive game, helped by a core of former Basque players who had moved to Andalucia. This strength was reflected in their opening five matches, which all resulted in victory with just one goal conceded. Betis hit the top of the league in Week 3, and remained top going into the final fixture, away to Racing Santander. On the evening before the match in Santander, O’Connell met with Racing’s officials, having managed the club for seven seasons from 1922. The next day, Betis romped to a 5-0 victory. Real Madrid protested that O’Connell had bribed his old team to throw the game. Betis, in turn, accused Real Madrid of offering Racing a win bonus. The result stood, and Betis took their first and to date, only league title.

Back in 1929, Sevilla hosted a major Ibero-American trade fair, which led to the construction of a new stadium in the Heliopolis district of the city. With an 18,000 capacity, this open, square-sided arena was ideally suited to the up-and-coming Betis. Whilst Betis played a few games at Heliopolis and several accounts have them in situ from 1929, the club continued to play their home matches at Patronato until the end of the 1935-36 season. Despite winning the league title, the club’s finances were in a poor state. Therefore, in 1936, the club reached an agreement with the Municipality, which owned both plots of land, to switch to Heliopolis. The timing of the agreement could not have been worse. Signed on 15 July 1936, the Spanish Civil War began 48 hours later, and with it, fighting broke out in the streets of the city. Betis had played their last match at Patronato on 24 May 1936, drawing 0-0 with Osasuna in the cup. The pitch at the old ground continued to be used for football, but the main stand and terraces had long disappeared by the time garages for the local bus company were built on the site in 1974. However, you can still find a trace of Real Betis’ presence, as those old tennis courts that stood behind the north terrace at Patronato are now the location of the Real Club de Tenis Betis on the Avenida Ramón Carande.

1 thought on “Sevilla – Campo del Patronato Obrero”

Comments are closed.