As you are probably aware, many European leagues allow reserve teams to compete in all but the top divisions. Spain is no exception, and over the years, this has thrown up many intriguing accounts of mergers, divisions, and, very occasionally, direct encounters with the parent team. Real Madrid-Castilla has experienced all of these in its chequered past, including a famous encounter with the first team, but first of all, let’s look at how they came into being.

Within a couple of years of its foundation, Real Madrid had established a network of relationships with smaller, local clubs that ensured that they had first refusal on any promising players. Among those first clubs to enter into the fold were Amicale del Liceo Francés and Moderno FC. As the club’s stature grew, so did its catchment area and the number of associated clubs. By the 1920s, Racing Club de Madrid, Real Sociedad Gimnástica Española, Castilla Foot-ball and Unión Sporting Club had all joined the congregation. On 16 December 1930, Pablo Philip and Agustín Martín formed Agrupación Deportiva Plus Ultra, the multi-sports association of the Plus Ultra Insurance Group. Initially, the club’s football section competed in competitions specifically organised for businesses, but in 1943, they changed its charter and joined the Castellana Federation. Plus Ultra also purchased the old velodrome at Ciudad Lineal in 1943, which had briefly staged Real Madrid’s first team matches some twenty years earlier. After making rapid progress in the regional leagues, the club earned promotion to the Tercera in 1946-47. Then Real Madrid came a-calling.

After a steady start to life in the Tercera, AD Plus Ultra became an affiliated club to Real Madrid in 1948. The additional financing and expertise paid immediate dividends as the Tercera title was won in 1948-49 and, with it, direct promotion to La Segunda. AD Plus Ultra made an impressive start to life in the second tier, finishing third in Group II, as well as reaching the third round of the Copa del Rey. The club became the sole affiliated club and unofficial reserve team to Real Madrid in 1952, but then experienced the downside of its relationship. Players such as Zárraga, Grosso, Miguel Muñoz and Casado had all progressed through the ranks to the first team, but this left the AD Plus Ultra with inexperienced players who could not cut it in La Segunda. Relegation to the Tercera followed in 1953, and the club spent three of the next four seasons at that level.

The Ciudad Lineal underwent redevelopment in 1956 with the removal of the track and development of terraces to the north & east. The next group of quality youngsters arrived in the late 1950’s and they reached their peak between 1958-60, reaching the quarterfinals of the Copa del Rey and finishing fourth in Group II of La Segunda. Relegation followed in 1963, and the club endured a period of relative disappointment. The stadium was renamed the Estadio Antonio Borrachero in 1966, after the former president of the Plus Ultra group. The stadium was renovated in the early 1960s, and a 70-metre-long cantilevered roof was added along the northern side of the ground, and large terraces were featured on the southern side and the eastern end. The Spanish Olympic team played Iceland in a qualifier at the stadium on 22 June 1967. The Tercera title was won on three occasions in the 1960s, but performances declined and following the demise of the Plus Ultra Insurance Group and its associated social clubs in 1972, Real Madrid acquired the club’s licence and set up Castilla Club de Fútbol.

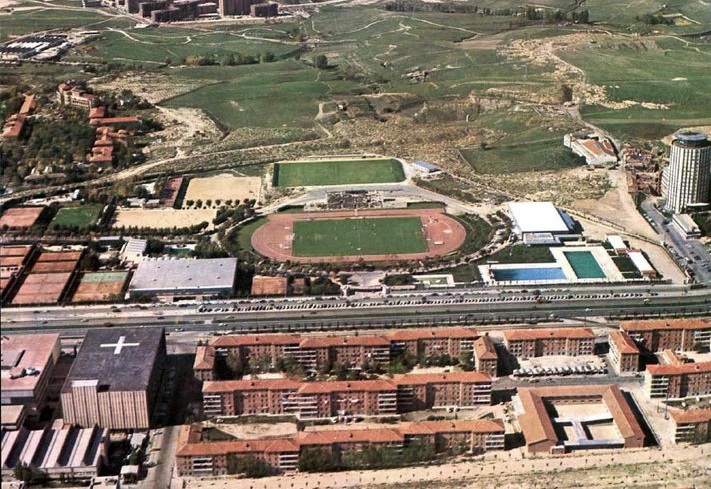

Now officially the reserve side, the new club moved from Ciudad Lineal to the Ciudad Deportiva, Real Madrid’s training complex, a mile or so north of the Estadio Santiago Bernabeu, on the Castellana. The sports city was opened by Santiago Bernabéu & General Franco on 18 May 1963 and also featured basketball, athletics, tennis and swimming facilities. Whilst results improved under the new structure, promotion proved elusive, but help was at hand when the Spanish Federation restructured the leagues for the 1977-78 season, and Castilla CF’s fourth-place finish in the Tercera was enough to earn a position in the new Segunda B. The club finished as runners-up in the inaugural season, earning promotion to La Segunda, an elevation that would start the most remarkable phase in the club’s history.

Castilla FC’s form in their first two seasons back in the second tier had been consistent, with two seventh-place finishes. However, it was their run in the 1979-80 Copa del Rey that captured the nation’s imagination. The club played an incredible 14 matches, beating first division Hércules CF, Athletic Club, Real Sociedad and Sporting Gijón before meeting their parent club, Real Madrid, in the final at the Santiago Bernabéu. There was no fairy tale finish as the first team ran out 6-1 winners. Castilla’s reward was a place in the following season’s UEFA Cup Winners Cup, where they drew West Ham United. On 17 September 1980, Castilla beat West Ham 3-1 at the Bernabéu, but the match was marred by crowd trouble from the travelling support. Two weeks later and behind closed doors due the UEFA’s sanctioning, West Ham beat Castilla 5-1 after extra time. The 1983-84 season saw the club surpass any previous league form and finish top of La Segunda, ahead on goal difference from another reserve team, Bilbao Athletic Club. As we all know, reserve teams cannot play in the same division as their parent club, so the third, fourth & fifth placed teams were promoted to La Primera. As the top players from this golden age, such as Martin Vazquez, Miguel Pardeza, Manolo Sanchis, Michel and Emilio Butragueno, moved up to the first team, Castilla’s fortunes declined. Aside from three appearances in the quarter-finals of the Copa del Rey and a third-place finish in the 87-88 seasons, form was patchy, and in 1990, the club dropped back into Segunda B.

In 1990, the Spanish Federation modified its regulations, dictating that all clubs in the top two divisions become either limited companies or registered membership associations. This, in turn, meant that all affiliated teams of a professional club must be assimilated into the professional club. This led to the dissolving of Castilla CF, and in its place rose Real Madrid Deportivo. It was business as usual on the pitch as the club won the Group I of Segunda B and the subsequent play-off group and returned to La Segunda. Over the next six seasons, there were flashes of the form that saw their predecessors achieve so much, but a fourth place finish in 95-96 was as good as it got and at the end of the following season, Real Madrid B, as they were now known, had dropped back to the third tier. Thoughts off the pitch centred on the ageing Ciudad Deportiva, which was now surrounded by Madrid’s booming financial district. With mounting club debts, the club was keen to sell, but there was a problem. The Ciudad Deportiva was built on land that was specifically allocated for non-commercial use, and it took some wheeling and dealing, which included the club giving the government a portion of the land, before they were able to sell and redevelop elsewhere.

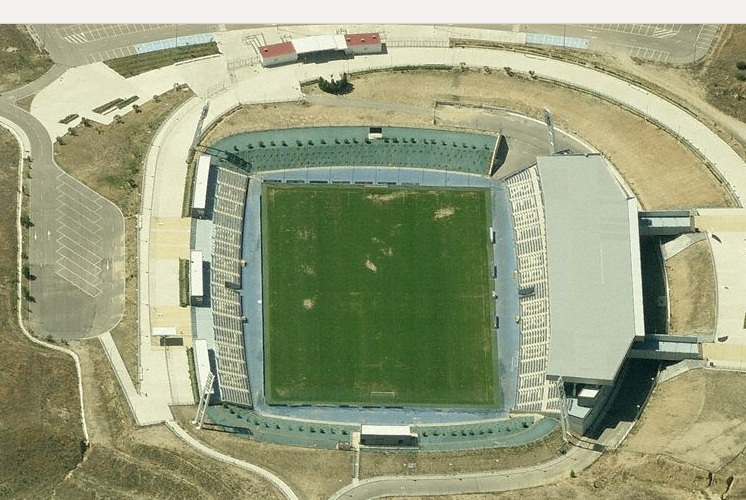

Real Madrid’s new sports city was located 6 miles northeast of the city centre, near Valdebebas. Benefiting from the 480m euros the club made from the sale of the Ciudad Deportiva, no expense was to be spared in developing the world’s largest and most lavish training complex. Real Madrid B moved in towards the end of the 2003-04 season and used one of the smaller pitches to the northeast of the complex. This had a capacity of just over 1,500 and would be home for just under two years. In July 2005, the team adopted a new title, Real Madrid Castilla and took the new name into La Segunda for the 05-06 season. On 9 May 2006, Real Madrid opened the centre-piece of their sports city, the Estadio Alfredo di Stéfano. named after possibly their greatest-ever player. In a nice touch, the inaugural match saw Real Madrid’s first team take on Stade Reims in a rematch of the first-ever European Cup Final.

Only Real Madrid & Barcelona could invest so much into a stadium for their reserve sides. However, whilst Barca’s Mini Estadi was a piece of 1980s functionality, the Estadio Alfredo Di Stéfano is 21st-century cutting edge. It may only hold 6,000 spectators, but it is tailored to meet the needs of the modern player and media hacks. It is also the greenest stadium in Spain, with recycled water used to nourish the pitch and solar power providing 60% of the complex’s electricity. From a spectator’s point of view, the stadium is comfortable, and the main stand on the west side is quite impressive, but in reality, it isn’t terribly exciting. With spectators confined to the main stand and the open east bank, it does feel unfinished, but the current structure does allow for either end to be developed, along with the addition of a covered stand on the east side and an extension of the main tribuna. But does Real Madrid need a 20,000-seat stadium for its reserve team in the middle of nowhere? In reality, with Castilla flitting between the second & third tiers, the stadium will almost certainly remain unchanged.

Following the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic and to enable the ongoing renovations at the Estadio Santiago Bernabéu, Real Madrid’s first team switched their remaining home fixtures of the 2019–20 season to the Alfredo di Stéfano. Matches were played behind closed doors, starting on 14 June 2020 with their match against SD Eibar. On 6 September 2020, still behind closed doors, the ground hosted the Spanish national team for the first time when La Selección beat Ukraine 4-0. The stadium continued to host the First XI’s games without spectators throughout the 2020–21 season before returning to the Estadio Santiago Bernabéu for the start of the 2021–22 Season.